Blog

Communicating the Message of Jesus in a World of Spin

8 August 2010

An Address to the Friends of the Church of Saint John the Baptist, Canberra

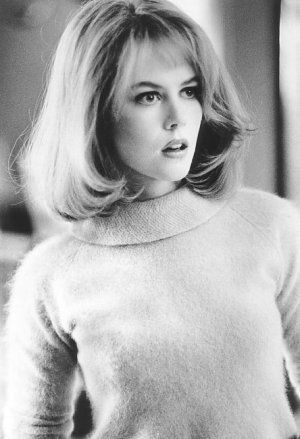

The film in which Nicole Kidman first demonstrated what a fine actor she is was the 1995 movie To Die For, a sardonically dark comedy about Suzanne Stone, a beautiful, but cold, calculating, ruthless, shallow and above all ambitious young woman who is prepared to go to any lengths – including having her husband murdered – to attain national fame as a TV presenter and anchor-person. For her ordinary domestic life is more than nothing; it is non-existence. Her only reality is the attainment of fame and celebrity. In the course of this extremely well-scripted film she utters some classic lines including “You’re not anybody in America unless you’re on TV. On TV is where we learn about who we really are. Because what’s the point of doing anything worthwhile if nobody’s watching? And if people are watching, it makes you a better person.”

The film in which Nicole Kidman first demonstrated what a fine actor she is was the 1995 movie To Die For, a sardonically dark comedy about Suzanne Stone, a beautiful, but cold, calculating, ruthless, shallow and above all ambitious young woman who is prepared to go to any lengths – including having her husband murdered – to attain national fame as a TV presenter and anchor-person. For her ordinary domestic life is more than nothing; it is non-existence. Her only reality is the attainment of fame and celebrity. In the course of this extremely well-scripted film she utters some classic lines including “You’re not anybody in America unless you’re on TV. On TV is where we learn about who we really are. Because what’s the point of doing anything worthwhile if nobody’s watching? And if people are watching, it makes you a better person.”

Written in the early-1990s these words have now become literally true with so many people featuring on their own social networking sites such as FaceBook (more than 500 million active users), MySpace (130 million active users), Twitter (75 million active users), and the one I like most, aSmallWorld (550,000 active users), an invitation-only European-based site for upper-class snobs whose unique selling point is that the lower orders can’t join! There are literally hundreds of other such sites. Here everyone has their own minor cult of celebrity; they can project their image, express their opinions and actually become ‘somebody’ in Suzanne Stone’s philosophy. Facebook and the other social networking sites simply assume that there is no point in “doing anything worthwhile if nobody’s watching” thus making yourself “a better person.”

The sheer proliferation of these social networking sites leads straight into the question of content. Over the last decade and a half we have developed a mind-boggling array of ‘platforms’ (i.e. channels of communications), a vast array of media choices, but have paid less and less attention to content. So many means of communication, so little to say! We have lost the role of the editor, the person who assesses the comparative importance of stories and ranks them in terms of public interest. The editor should also point to neglected stories.

George Steiner, one of the finest critical minds of our times, says that “The uses of speech and writing current in modern Western societies are fatally infirm. The discourse which knits social institutions, of legal codes, of political debate, the leviathan rhetoric of the public media – are all rotten with lifeless clichés, with meaningless jargon, with intentional or unconscious falsehood.” He speaks of “the pathologies of public language, especially those of journalism, of fiction, of parliamentary rhetoric and international relations” (Real Presences. Is there anything IN what we say?, London: Faber and Faber, 1989, pp 110-11). And Steiner wrote that long before the advent of the proliferation of social networking sites and media platforms.

The fact is that communication, language and metaphor have become so debased in our culture that the discourse which should bind us together has in fact become fundamentally mendacious and divisive. This mendacity is vividly illustrated by the debasement of language and the meaning of words in common use. Advertising, particularly, has taken significant words and images and twisted them to represent totally unnecessary and useless products. It is about consumption for consumption’s sake. As Don Watson pointed out in Death Sentence. The Decay of Public Language (Sydney: Random House, 2003) contemporary speech and writing is littered with jargon, clichés and euphemisms. What Steiner calls the “leviathan rhetoric” of the media is a never-ending and confused flood of the trivial and significant, the relevant and the banal, truths, half-truths and lies, all cobbled together without the slightest discrimination between what matters and what does not. At heart much of our civic rhetoric is mendacious. The American critic Theodore Roszak says bluntly that our culture is “toxic”. The irony is that in a world full “words, words, words” as Hamlet says, we have, like Polonius, lost the ability to communicate with integrity. While we continue to develop an extraordinary number of diverse means of communication, we actually have nothing significant to say.

The result is that we live in post-modern world full of talk-back radio and bloggers where every ‘message’ is given equal value and everyone is an immediate ‘expert’, no matter what their expertise or lack of it. Everyone has a right to express an opinion which is given equal weight to that of people who have devoted years of professional training and study to the matter in hand. This new, pseudo-democratic, popular, participatory culture has become, at its worst, an insane blogging free-for-all where the most extreme, ill-informed and sometimes noxious views are expressed and people’s reputations thrashed. Certainly there are places on the net that are expressions of genuine democracy. But even the best of these can become relatively incestuous where people can support each other but sadly at the same time re-enforce prejudice.

By now you probably think I’m an antiquated hack who is quite jaundiced about the media. Actually, I’m not. I’ve spent the last 30 years in this world trying to communicate the message of Jesus and the tradition of the church. However, while I think we have to be utterly realistic about the world of communications in which we live, I’m not one of those church people who feel badly treated by the media. Some Christians feel that the church’s strengths and successes are never covered, but are buried in a morass of bad publicity. For instance in their 2006 Pastoral Letter on the Media Australia’s Catholic bishops, complained that “the Church has suffered at the hands of the media ... Often, the Church is singled out for criticism because its message is profoundly and radically counter-cultural in this secular age.” The bishops are certainly kidding themselves about the church’s counter-culture stance, and it’s an old chestnut for churchmen to blame “secularism” for their own dismal failures to communicate the Christian message.

Another example: during the 2010 election, Perth’s Roman Catholic archbishop Barry Hickey was critical of Julia Gillard’s atheism. Contextualising his comments Hickey said he was concerned about what “the future will bring if secularism is allowed to take an unchallenged hold in our society. Encroaching secularism in our society could lead to social policies that are harmful to the good of our society and personal well being. This is already becoming evident in some European countries and even here in Australia.” This is a bit rich coming from a church that is still caught up after 25 years in the sexual abuse scandal and its consequent cover-up. It’s about time the church put its own house in order.

Certainly most journalists reflect the secular, small ‘l’ liberal view of the world and are not particularly church-friendly. Nor are they well informed about Christianity specifically or religion generally and they are often influenced by stereotypes and caricatures of the church. Outside the Religious Department of the ABC which now employs only a tiny pool of five specialists, there are only about two or three other well-informed religious journalists working for Australia’s daily newspapers. Part of the problem is that most current affairs journalists have to cover different stories every day, often at high speed with a minimum knowledge of the facts and a complete lack of understanding of the broader context.

They are also often frustrated by bishops and church spokespersons that refuse to make any statement, sometimes on the most innocuous issues, or who, when they do talk, are often defensive and overly cautious. The church doesn’t seem to understand the dictum: “if you don’t control the story someone else will.” And the church’s defensiveness has been exacerbated by the sexual abuse crisis; the church’s reputation has been very badly tarnished by this issue. Essentially the problem is that both the church and journalists harbour ill-informed stereotypes of each other. They see each other in oppositional terms.

The Age religion reporter, Barney Zwartz has pointed to some of the difficulties that the informed religion reporter faces. “There are hardly any religion specialists in the media in Australia, there is no instructor, and it’s a subject that often inspires strong passions.” He outlines the essence of the task: “I have to satisfy the editors not that a story is worthy, but that it is newsworthy, a much harder task. I have to present it powerfully, bring out the controversial aspects, so that people will understand why it is important. I have to be fair, accurate and balanced, and provide context.” He points out the religion reporter also has to deal with religious communities under siege, like Australian Muslims. Also many journalists are fixated on particular stories which are covered relentlessly. “When I took the job, there were three main religion stories”, Zwartz says. “One, the Church is dying. Two, the troglodyte church gets in the way of gays and women. Three, priests and paedophilia. All of these are important, but if that’s all you ever write about you’re missing the story.”

We also have to remember that the media is a social construct. The use of the word ‘story’ is the clue here. Because even news media (especially commercial TV news and current affairs and increasingly the ABC) is essentially a form of entertainment, each issue covered has to be told in a narrative form. Thus a story is constructed which identifies the constituencies and interest groups in the issue or debate, analyses their motives and interests, makes judgments on the basis of contemporary mores and what is socially acceptable and politically correct at the time, all eventually leading to the selection of the good and the bad, heroes and villains. There is also a strong element of ethical righteousness and even pharisaic priggishness in journalism; journalists often set themselves up as the arbiters of morality – with no justification whatsoever!

In fact when journalists do think about the Church – which is not very often – they usually think of the hierarchical churches as centralised, controlled, wealthy organisations which are not responsible to anyone except God, Who, when it suits the church, can be a remarkably long way away. Bishops, and more recently the Vatican’s behaviour in the sexual abuse crisis, have encouraged this attitude and there is a conviction abroad that the church has deliberately sheltered large numbers of paedophile priests and sees itself as above the law. Even at the best of times the church is seen as a kind of ‘colour piece’, a human interest story of no great significance. Not knowing Christianity’s long and articulated moral and intellectual tradition, many journalists see the church as essentially fundamentalist. These are unconscious, unarticulated stereotypes and not everybody holds them in their entirety, but they do act as caricatures that impregnate the whole interaction.

From the perspective of the leadership of the church I think the essence of the problem lies in an apparent inability to enter into what might be called ‘public discourse’. Bishops and church leaders are good at issuing statements, many of them cogent and worthwhile. But where the failure comes is in defending and discussing the church’s stances in public discourse. Democratic societies have evolved fairly sophisticated skills in the formulation of policy, as well as an ability to balance the conflicting and often contradictory expectations of the many competing groups that make up complex, modern, elective, parliamentary states. This is achieved through public discourse. In this kind of context genuine leadership in our society does not just involve issuing statements or making stands. It demands active participation in a broad public dialogue about one’s beliefs and stances. It involves having convictions and being willing to express them clearly and cogently. These convictions can be passionately held and strongly expressed. But public dialogue demands that participants not only hear other views, but respect the right of others to hold their views, however vigorous the disagreement. It implies a willingness to play the democratic game and to participate in the democratic process.

This creates considerable problems for a church that makes claims to possess ‘The Truth’. In this new participatory culture it is from this interaction that public policy and opinion can emerge. Over the last two decades there has been a significant failure by Christians, with a few prominent exceptions, in engaging with other views in serious media debate. We are good at issuing statements and pontificating upon them, but we are generally inept at debating and defending our stances in the face of conflicting opinions and attitudes.

Even more deeply entrenched is the media’s assumption that the Church has nothing significant to say on the issues that trouble people today. Geraldine Doogue recently pointed out in a Catalyst for Renewal paper that The Australian Financial Review annually gathers 25 “interested observers to assess who are really powerful in Australian public life, those who affect the course of debate and set their own agenda.” She observed that “not one [of these agenda setters] mentioned anyone in the churches, which is an interesting benchmark about attitudes.”

But why aren’t religious people called on to talk about questions of meaning, ethics and spirituality? Partly for the reasons stated above, but also because, as Doogue says, “those who are used as sages, as providers of genuine help and clarity when people need it in terms of making sense of their lives, are usually the psychologists, writers and artists ... [They] use language that really can unlock deep and profound road-blocks in contemporary mind-sets and satisfy searchers for ways ahead.” She refers specifically to people like novelist David Malouf, feminist Eva Cox, social commentator Hugh Mackay, the American psychologist Martin Seligman and interfaith minister Stephanie Dowrick. Doogue correctly points out that these people are actually using “a profound reservoir of thoughts which draw on the great Christian tradition.” Doogue’s judgment is that our culture “is not a value-free, conscience-free zone at all. Quite the reverse. There is plethora of searching, overtly and covertly underway, with quite elaborate and imaginative forums being devised.”

I would also argue in Australia there is a strongly-secular, generally left-leaning ‘gate-keeping’ class that, either consciously or not, maintains control of who has media access and who doesn’t. These are the people who often write for The Monthly or Quadrant. They make sure that they are consulted about public issues and are always the first to have an opinion piece ready for the print media.

However, I think Doogue puts her finger on the key issue when she says that influential people “use language that really can unlock deep and profound road-blocks in contemporary mind-sets.” This is why the church is often left out of the discussion. We have lost the language or rhetoric that speaks to people today; we have not been able to translate our great Christian tradition into speech that makes sense to our contemporaries. Clearly there are exceptions to this like Father Frank Brennan and Rev. Tim Costello, but they are few and far between.

In order to participate in this kind of deeper discussion in our society you have to reach outward and find common ground and use contemporary rhetoric. You need to hear the spiritual/meaning questions that our contemporaries are asking. Often they are camouflaged in an inarticulate jumble of other issues. Then you need to draw on the teaching of Jesus and the Christian tradition to begin to address those questions. This is really a form of what theologian Alfonso Nebreda calls ‘pre-evangelisation’. Pre-evangelisation is essentially the creation of an atmosphere in which belief and religion is seen as important, so that it should be as much part of public discourse as politics, economics, foreign affairs, social policy, health and the other issues the culture takes seriously. In theological terms pre-evangelisation prepares the ground, awakens a sense of the possibility of access to the Transcendent and spiritual. It takes people where they are, but indicates a way forward to faith.

But pre-evangelisation has become much more difficult because a single issue has increasingly defined the relationship of the church and the media: sexual abuse. It has become THE story and seemingly endless revelations about priest abusers and episcopal cover-ups have understandably pushed Christians into a defensive stance. The result is that the church is popularly perceived as a corrupt, abusive institution that is plagued with an epidemic of abuse and untruthful bishops. There is a real danger that the sexual abuse crisis will infect the church’s response not only to the media but to contemporary culture generally. It has thrown the church on the defensive. In a thoughtful article US Vatican specialist John Allen has commented that church leadership under Benedict XVI has retreated from the task of “culture-shaping” – or what I have called pre-evangelisation – and that “policy-makers in the church, particularly in the Vatican, will be ever more committed to what social theorists call ‘identity politics’, a traditional defence mechanism relied upon by minorities when facing what they perceive as a hostile cultural majority” (National Catholic Reporter, 2 July 2010). If this is true it is a tragedy because part of the church’s catholicity lies in its openness to the surrounding culture. To take a defensive stance is to critically harm its evangelising mission.

The media is the world that I’ve personally inhabited for the last thirty years, a secular world in which I saw it as my primary task to keep religion – and specifically Christian faith – alive in public discourse. This, in my view, is the challenge we all continue to face in the church. We can either retreat back into ourselves, into a form of identity politics that is essentially sectarian, or we can in a genuinely small ‘c’ catholic sense continue to engage in critical dialogue with the culture around us. In my view to retreat into a sect is to betray the Gospel and the call to ‘teach all nations’.

Care to comment? .